A special project for 92Y Unterberg Poetry Center’s 75th anniversary and beyond, 75 at 75 invites authors to listen to recordings from our archive and write a personal response. Here, Pura López-Colomé writes about two readings by Seamus Heaney. They were recorded live at 92Y on March 22, 1971, and September 26, 2011.

Posted on April 13, 2015

I was fortunate enough to hear Seamus Heaney read his poetry many, many times. In person and on recordings, on his own and accompanied by others, for small audiences and big ones, some of them huge. In different latitudes, even. On his second public appearance in Mexico, where I am from, there were giant screens placed along the streets surrounding the auditorium and people sitting on top of buildings.

I was fortunate enough to hear Seamus Heaney read his poetry many, many times. In person and on recordings, on his own and accompanied by others, for small audiences and big ones, some of them huge. In different latitudes, even. On his second public appearance in Mexico, where I am from, there were giant screens placed along the streets surrounding the auditorium and people sitting on top of buildings.

Before speaking about these two recordings, the first and last readings he gave at the 92nd Street Y’s Poetry Center in New York, I want to say something about an aspect of poetry we both believed in. Since early on and often when we spent time together, we talked about the prophetic-didactic quality of poetry, of the ear tuned to a certain “voice,” revealing or teaching something essential. Consequently, he asserted, one should be very careful with what is articulated in a poem. Poetry does survive. It’s “a way of happening, a mouth,” a sort of oracle nourished by the poet’s questions.

So many prophetic glimpses! I remember a particular morning during my first visit to Ireland, strolling with Seamus through Glendalough, not talking, merely listening to the sounds of running water, and suddenly turning and looking at each other, reciting at exactly the same time these lines of Wordsworth: “Was it for this / That one, the fairest of all rivers, loved/ To blend his murmurs with my nurse’s song, /And, from his alder shades and rocky falls, / And from his fords and shallows, sent a voice / That flowed along my dreams?”

So, trying to make some sense out of this, I ask myself here and now: Was it for this that I met Michael Ondaatje during my recent stay in Canada, gave him my last book, after which he, in turn, invited me to participate in a reading he curated at the Y, the closing scene of all this being asked by the Poetry Center to write about my memories of Seamus Heaney? Certainly there is a governing power in poetry. However, in order to explain the privilege I’ve been given, I must appeal to the fact of it being “more a threshold than a path, one constantly approached and constantly departed from, at which reader and writer undergo in their different ways the experience of being at the same time summoned and released.” I feel summoned now, knowing I will be released only when I am summoned again.

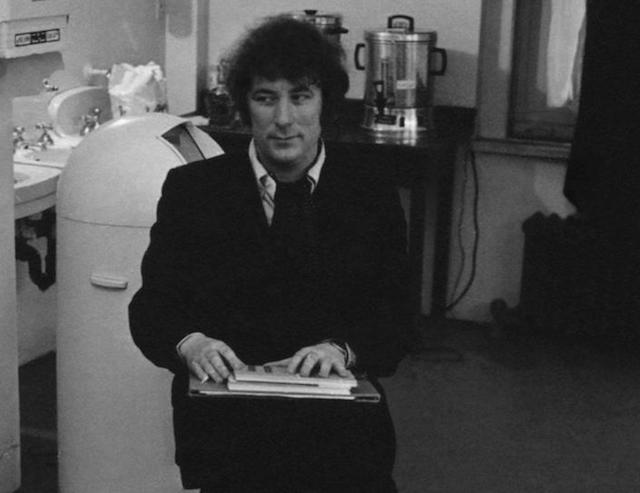

Seamus Heaney backstage at 92Y on March 22, 1971. Photo by Jack Prelutsky.

Heaney is in his early thirties on this 1971 recording, already in full command of his capacities—a Beethoven, more than a Bach. I hear him reading (reciting by memory, I am sure) “Personal Helicon,” a poem he let float in the air, as if it were a mantra, probably in the majority of his stage performances, or at least in all those I attended. It’s as if he needed to connect with Northern Ireland, that personal place of origin from the title, as well as with the mount of poetic inspiration where Narcissus fell in love with his own image. In this young voice, I hear the pendulum move from danger to caution; from overdoing things, being egocentric, forgetting that it is only a reflection of the godly aspect in humans, to the risky extreme of being blinded, like Tiresias, punished but also endowed with the art of prophecy. Will honest renouncement bring something secretly better? The poet-visionary’s vibrant voice, about to be swallowed by dichotomy, banishes all evil through a salutary tension coil he was born with, a true sense of humor. During this particular evening, after reading the poem for a breathless audience, he jokes about a supposed misprint in “big-eyed Narcissus,” where the line should have said “bog-eyed Narcissus.” The audience laughs. Seconds later they are breathless once more. Very new to me in this recording, though, is his “bardic” way of reading—a Dylan Thomas sort of chant.

This reminds me of the first time I heard him in person, in 1981. It’s ten years later, the voice is almost intact. During his first visit to Mexico, several group readings were organized: Borges, Paz, Grass, Tranströmer, Ginsberg. I hitchhiked all the way from Mexico City to Morelia, mainly to listen to Ginsberg, with whom my generation was infatuated at the time. He was supposed to be reading, singing and playing an exotic instrument on stage! That night, I happened to sit next to Tomás Segovia, great poet and fatherly figure who, on seeing I was planning to write about Ginsberg for the newspaper supplement where I had a regular column, whispered in my ear: “Listen to Heaney first. He’s the one you should be translating.” Some of his poems had already been translated for the festival by a fellow poet, so I was lucky enough to be dazzled as a mere listener and I immediately plunged into his work. The more I read, the clearer it became that translating his poetry was not a question of transposing meaning and metaphor. This was something deeply rooted in sound, to which even plurality of meaning was subordinated, not the other way around. It would be unthinkable to separate one from the other. How could I “dare frame” that perfection in Spanish, whose sounds are not similar, whose uttering, as it were, follows the Latin pronunciation to the extemes of the mouth and out, instead of gutturalizing, internalizing, the way English does it (and most likely Anglo-Saxon)? The epiphany would come much later, precisely through the Latin bond. Listening to his 1971 reading, I confirm it through a small example: “Undine.”

Everybody knows how comfortable Heaney always was on stage. Since the very beginning, he knew poetry could not, should not be explained. However, in order to be fixed in the ear and in the affections of the listener, the human being that wrote it should manifest his or her own flesh and blood as such. Thus, he generally offered a tangible context, spoke about the thematic conditions surrounding the actual putting into words of the poem, its landing on earth. In the case of “Undine,” instead of first talking about the actual water nymph, and/or her connection with his own experience, he decided to linger on the power of sound, mere sound as what gave verbal form to the creature. The poet repeating “Undine, undine, undine” in 1971 opens my ears in 2014 and throws my psyche into the depths of the “was-it-for-this” motive for the actual birth of his poems in my language. “Undine” is, in fact, a Latin word, original source of the Spanish word “Ondina,” meaning a creature of the waves “Unda” grants us “onda”—a bit distant from the English “wave,” right? Latin, the language Seamus loved so much as to use it in his last words to his wife, Noli timere, triggered this particular poem. One of my strongest links to him and his poetry.

The first book of his that I translated in its entirety was Station Island. I really did my best, knowing it would only be a tribute from my side of Babel. He was happy with it, enthusiastically praised every detail, even the “physicality” of the book itself. Nevertheless, I distinctly remember him saying (this was 1990): “Even though our shared grounds are Latin and Catholicism, don’t forget, my dear, that I was born to be translated into Dutch.” God. Finders keepers. Everything I needed to know was inside that last phrase. The most important aspect of poetry is the sound of the language that produces it—exactly what makes it untranslatable. Dutch and English, in terms of sound, have a lot in common, just like Spanish and Italian. And here I was, aiming at the unattainable! What he was trying to tell me was: Even though what you’re doing is commendable, a recreation, a making-it-new of the poem, a making it born in another sphere, using all the resources owned by your language, sound is preeminent. So, if you insist, at least prevent it from drowning by holding on to form, taking advantage of it, being faithful to it: “Poetic form is both the ship and the anchor . . . The form of the poem is crucial to poetry’s power . . . to persuade the vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it.” These words, part of his Nobel Lecture that I would translate much later, were my life-savers, what kept the Spanish body afloat in the books that followed, in spite of the loss of gutturals and the new, rather noisy presence of open vowels, the watery sounds of a nymph, my very own “Ondina.”

The person who introduced Heaney in 1971 spoke about his style, his themes, his roots. The early audience, fairly new to the poet, needed bearings. As time goes by, very few poets keep those same initial characteristics, the language density as well as the subject matter, from first book to last, from first reading to last. Perhaps the only difference, the only sign of “evolution,” is the construction of a richer, more inclusive, poetic space, in which the new turns old, the old turns new. Very few.

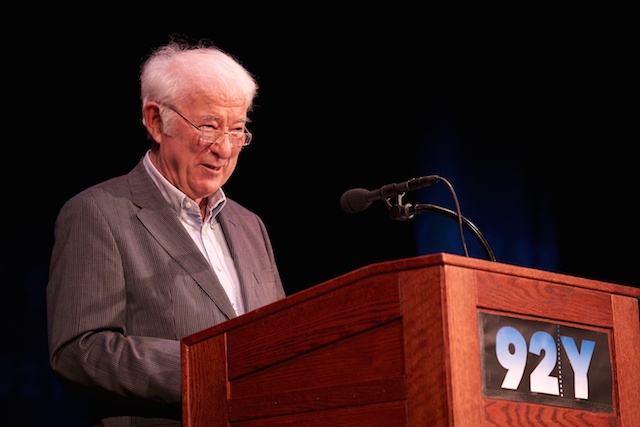

Seamus Heaney on stage at 92Y on September 26, 2011. Photo by Nancy Crampton.

By the 2011 reading, and obviously well before that, he was a poet who really needed no introduction. He had already given the English language, as Shakespeare said, “a local habitation and a name.” Both the person and the work seem approachable from every possible angle. After his death, there were videos everywhere, specifically in the English-speaking world: Ireland, Canada, Australia, the US, the UK. Among so many tributes, a couple come to mind. Bernard O´Donoghue, for instance, or Roy Foster, who, after talking extensively about Heaney’s literary achievement, mention the fact that he always had something great and personal to say to everyone, concluding that he belongs to all of us. How happy I am to include myself in this group, to feel a part of “all of us there.”

In its seventies now, the voice in 2011 has grown deeper. It has shed the deliberately “bardic,” Dylanesque tone it showed traces of decades before. Although a bit shaky, it has definitely gained in power, in scope. This man has travelled through word and world. His voice, his vehicle, almost “otherworldly”—a strange adjective Seamus loved to use. This is the author of Human Chain, who has received a final call, gone to the limits, almost died and come back. This last reading is a generous mini-anthology of life and work, for new and old reader-listeners alike. The journey begins at his place of origin, under “Mossbawn Sunlight.” Then it stops at the shores of contradictions experienced by the individual, vis-à-vis the Northern Troubles community somehow present in “Oysters,” seen by a man as full of life and its pleasures as his beloved Neruda in Tamlaghtduff. Then again it goes back to the personal, the familiar, remembering both parents, folding sheets with his mother, admiring his father’s plaiting of a harvest bow. His friends are also passengers on this trip, and his children, and even grandchildren: all his loved ones, the ones who “have known him all along/And carry him in,” conceived as the proper miracle. The place of honor is occupied by his wife and companion in life and near-death, ecstatically lifting his spirits by singing, via John Donne, about their adventure in this world.

I conclude this long personal elegy to Seamus’s personal Helicon by making special mention of four chosen poems, in pairs, that stand out for me in this 2011 reading, as they synthesize my own reading of his poetry in life, of his life in poetry. First, the “after-the-first-death-there-is-no-other” couple—“Mid-Term Break” (from Death of a Naturalist) and “The Blackbird of Glanmore” (from District and Circle). And second the “soul” couple—“A Kite for Michael and Christopher” (from Station Island) and “A Kite for Aibhín” (from Human Chain).

The first two have the central motive of death signifying the abrupt end of innocence by cutting off the life of a child. Death is not equal to the natural end of physical strength, but to the insertion of obscurity and loss in the realm of clarity, metaphorically concentrated, as it were, in a blackbird that for the poet fills everything with life, but in popular belief embodies the augury of darkness. In other words, life as such, in its very intensity, carries its own ill omen.

The last two are particularly dear to me because they belong to the first and last of his books that I translated. It seems to me that, after the final poem of Human Chain, Seamus just took off, “alone, a windfall,” as though that image of the kite as soul was really part of the person who envisaged it. This sounds as terrifying as all things spiritual—this is what the phrase “fear of God” means, at least for every true poet: what John of the Cross called “el amado en la amada transformado,” the loved one in the beloved transformed. And it so happens that this last poem I´ve been referring to is what Seamus himself, in this last reading at the Y, called an appropriated version, a “Hibernicized” Pascoli poem. The actual inspiration for this most typical Heaney poem was “L’Aquilone,” by a late nineteenth-century Italian poet whose world simply coincides with Northern Irish country life. Being admittedly a translation, a recreation, in which Anahorish reality comes into contact with the contrast of kite and comet, in my version I allowed myself a contrast between the Castilian word “cometa” and the Mexican word “papalote,” originated in the name for butterfly in Náhuatl. Heaney was thrilled with my version, and in his praise he gave me an extra farewell bonus, as if my having translated his books was not a huge enough gift in this life. Oh, how I’d love to start translating his work at this stage of my poetic journey, when I can steadily hold on to the kite of form.

With an image of this very special bird (el mirlo) here in front of me, with awe, I offer a translation of the last lines of “The Blackbird of Glanmore,” my personal echoing darkness:

“On the grass when I arrive, In the ivy when I leave.”

“Entre el césped al llegar, Entre hiedras al partir.”

Pura López-Colomé’s most recent collection of poetry to be translated into English is Watchword. Her English-to-Spanish translations include works by Samuel Beckett, H.D., Virginia Woolf, William Carlos Williams, Gertrude Stein, Robert Hass, Robert Creeley and Seamus Heaney.