A special project for 92Y Unterberg Poetry Center’s 75th anniversary and beyond, 75 at 75 invites authors to listen to a recording from our archive and write a personal response. Here, J. D. McClatchy writes about a reading by John Malcolm Brinnin, director of the Poetry Center in the 1950s, upon the occasion of his centenary. It was recorded live at 92Y on November 16, 1964.

Posted on Sep 16, 2016

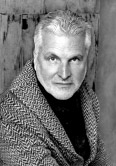

When I first met John Malcolm Brinnin, he was no longer a poet. Or if he still wrote poems, who knew? His last book of poems had appeared in 1970. By then—this was Key West in the 80s—he looked more like a pasha in his prime. Pleated white trousers and a gaudy tropical shirt distracted the eye from his paunchiness, while his own pair of enormous round, black-framed glasses cast a demanding gaze on whoever might then to speaking to him—most often at a drinks party at a friend’s home or in his own swank apartment. Among his Key West friends in those days were Richard Wilbur, James Merrill, Alison Lurie, John Hersey, John Ciardi, Frank Taylor and Rollie McKenna. But he seemed to spend less time there than they did. Always a restless traveler, much of his time was spent on the road. Wealthy friends adored his charming and witty company and were constantly inviting him to accompany them on cruises. He ended up going on so many that he became their connoisseur and historian. His several books on the grand ocean liners and the society that indulged them had come to preoccupy his time at the typewriter. And with age, his memories came to the front of his attention and resulted in books about them—Truman Capote, Elizabeth Bowen, Henri Cartier-Bresson, T. S. Eliot and others.

When I first met John Malcolm Brinnin, he was no longer a poet. Or if he still wrote poems, who knew? His last book of poems had appeared in 1970. By then—this was Key West in the 80s—he looked more like a pasha in his prime. Pleated white trousers and a gaudy tropical shirt distracted the eye from his paunchiness, while his own pair of enormous round, black-framed glasses cast a demanding gaze on whoever might then to speaking to him—most often at a drinks party at a friend’s home or in his own swank apartment. Among his Key West friends in those days were Richard Wilbur, James Merrill, Alison Lurie, John Hersey, John Ciardi, Frank Taylor and Rollie McKenna. But he seemed to spend less time there than they did. Always a restless traveler, much of his time was spent on the road. Wealthy friends adored his charming and witty company and were constantly inviting him to accompany them on cruises. He ended up going on so many that he became their connoisseur and historian. His several books on the grand ocean liners and the society that indulged them had come to preoccupy his time at the typewriter. And with age, his memories came to the front of his attention and resulted in books about them—Truman Capote, Elizabeth Bowen, Henri Cartier-Bresson, T. S. Eliot and others.

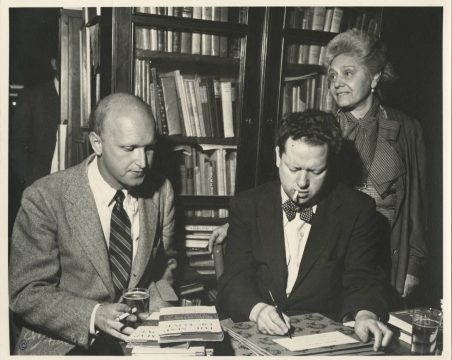

Whatever glamour attaches to poets had also to do with my first meeting with Brinnin, years earlier. Not an actual meeting, though it seemed as intimate, those hours I spent leafing through his 1970 anthology, The Modern Poets, a book he had edited with his lover Bill Read. Their editorial taste was impeccable, but it was the photograph of each poet by McKenna that drew me beyond the poems themselves and into the swirling drama of what went on in the imaginations of these fabulous creatures. There was John Betjeman wearing a suit that had once belonged to Henry James, John Ashbery dressed as a young hedge fund manager, May Swenson looking at a city tree as if she wanted to climb it, Auden’s cracking plaster. And all of them with cigarettes and shaggy hair. It was Parnassus sitting for its portrait, and it was Brinnin who had called the old and young gods together—as he had done for six years after 1950 as the director of the 92nd Street Y’s Poetry Center, a particularly starry era of its existence. He quite literally introduced American poetry to its public. Perhaps Brinnin’s most famous coup was luring Dylan Thomas to perform Under Milk Wood there. Bringing Thomas to the States—the Welshman’s food and drink, his fantasy and doom—became the story of Brinnin’s rousing and sad 1955 memoir, Dylan Thomas in America. Some think that his account of Thomas’s disintegration led to his withdrawal from the Poetry Center. Whatever the truth is, the four years Brinnin spent taking care of Thomas were a harrowing time.

(John Malcolm Brininn with Dylan Thomas at Gotham Book Mart in 1952)

All along, of course, he had been writing poems of his own. His first collection,

The Garden is Political, appeared in 1942. He was just twenty-six and fresh from graduate work at Harvard. Five more books followed. (The one to own is the 1963 The Selected Poems of John Malcolm Brinnin, published by Little, Brown.) His early work was a product of its time—its themes were serious (and sometimes religious), its rhetoric was intellectual, ironic, at time clotted. Throughout, he was in awe of his forbearers and their tradition. He wrote loving pastiches of Emily Dickinson, Edith Sitwell, W., H. Auden, Wallace Stevens and Gertrude Stein. There were affectionate tributes to the landscapes of his own past—particularly the Nova Scotia of his childhood. In later poems, his style loosens to its advantage. The time he spent in the Caribbean resulted in more vivid poems—“Nuns at Eve,” for instance, set on St. Martin’s, giddily describes a baseball game played by nuns—“They are all named Mary”—under a statue of the Virgin. But whenever he wrote light verse, he was at his best. Here are two stanzas from “Song from the Outer Office,” where a businessman wonders how he’ll spend his summer:

Sometimes Quebec still calls me back! Would the Hamptons help my status? Would Maine be the wrong step to take? Hyannis a hiatus? Oh, where shall I go this summer?

The Thousand Islands should be counted; Lake George should be canoed; If Provincetown’s half what it’s painted, I might return renewed. But where shall I go this summer?

He also knows how to work an image—that is, both to expand and deepen it. Here is a sonnet—a form he returned to often, with real mastery—about a simple snail. From the start, he works up his subject cleverly, and by the end has allowed real emotion to suffuse it. The poem is called “Architect, Logician.”

Architect, logician, how well the snail Narrates its tenuous predicament! Knit with fragility, its echoing cowl Enchants the space wherein he’s pent, Yet holds his heart like water in a bowl.

Like those who temper opal for a house, A wise man keeps the cosmos in his skull Rimmed with a box of sound where every day Repeats his wishing yet conforms him whole. As flesh grows merry in its neutral shell, Beware the pleasures of small bones that fit Elbow to brow when the design’s not whole; Each hauls his house; the trick’s to live in it.

There is another kind of sonnet he wrote. His snail sonnet is a precision-jewelled treatment of the object as symbol. “Waiting” is something altogether more oblique and moving. It juxtaposes an air-raid siren and a greenhouse, a threatening war and a white hibiscus. It was written in wartime, but doesn’t depict any situation then occurring in America. The war, in other words, stands in for any deadly threat. I would suggest that this poem is a homosexual love poem—and one of the best. The poet’s love is celebrated in the midst of every menace that threatens it.

What reasons may the single heart employ When, forward and impervious, it moves Through savage times and sciences toward the joy Of love’s next meeting in a threatened space? What privilege is this, whose tenure gives One anesthetic hour of release, While the air raid’s spattered signature displays A bitter artistry among the trees?

This, in our published era, sweetness lives And keeps its reasons in a private room; As, in a hothouse, white hibiscus proves A gardener’s thesis all the winter through, So does this tenderness of waiting bloom Like tropics under glass, my dear, for you.

J. D. McClatchy’s most recent book is Sweet Theft: A Poet’s Commonplace Book.